THE CHURCH OF THE BADIA. FLORENCE AND DANTE, 26 November 2006

Signorelli, Dante

Alinari

Augustus Hare

For this year’s Christmas Letter let me share the gist of what I said at the Mass for the Poor in the Florentine Badia’s church two Sundays ago. I began by saying Giovanni Boccaccio lectured on medieval Dante’s

Commedia in this very church during the Renaissance. And this was right because Dante grew up beside this church. When he was a child he would have heard the monks singing the liturgy of the Mass and of the Hours, Matins, Lauds, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers and Compline, as they had for centuries before him and as they still do here today. We hear these psalms and hymns in the

Purgatorio and the

Paradiso of the

Commedia. But not in the

Inferno, which is only filled with groans, sighs, screams, the discords of despair of those who have chosen to distance themselves from God.

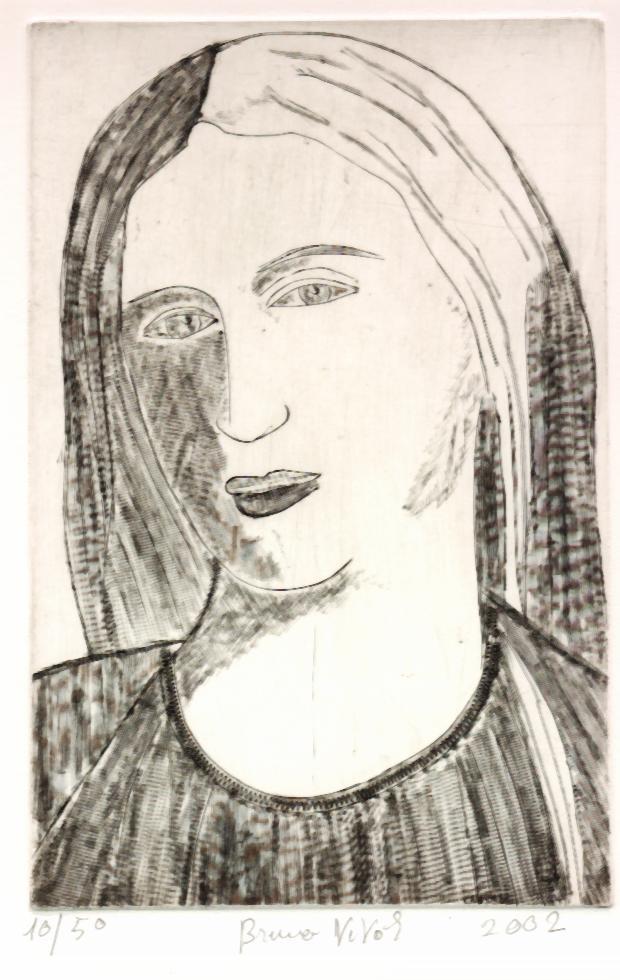

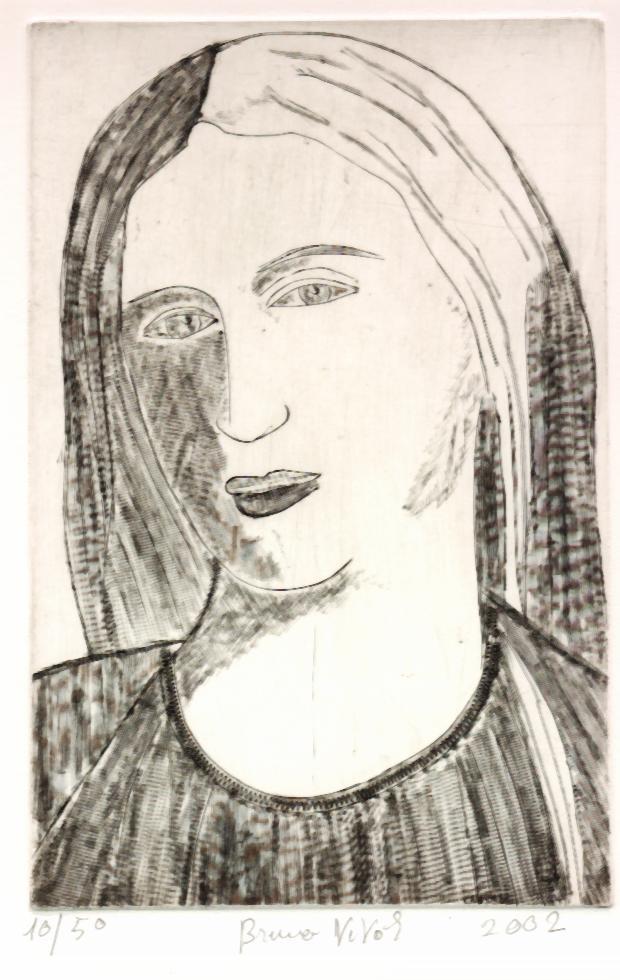

In Dante’s day, this church, which was part of an ancient monastery, was more beautiful. After Dante’s boyhood, but before Boccaccio’s time, it was rebuilt by Arnolfo di Cambio and filled with fine paintings by Giotto, the gold leaf dancing with the light of candles. The church later was completely changed and made shadowy in the baroque style. The beautiful tender Madonna with her Child, which recalls the numerous similes in Dante’s poetry about mothers nursing babies with their milk, was removed from the altar. It is now in the Uffizi; one may still see it but in a cold museum. Of these pictures below the first is by Giotto, the second by our Norwegian artist guest and it shimmers by candlelight in our library, and the third is by a participant in the Mass for the Poor, who would be so grateful if you would buy prints of it. It was Petter who taught Bruno how to print his engravings.

Giotto

Petter Sammerud

Bruno Vivoli

Dante tells us he wrote his

Commedia not in Latin but in Italian, so that even women and children could understand it, in Florence and in all of his Italy. Like the Gospel revealed to the lowly. Like St Francis’ Canticles. In his similes we find workmen and farmers, women and children, an old tailor threading his needle, a mother rocking the cradle and singing, pilgrims journeying from afar, workers in foundries and furnaces, and many many others. Dante remembers the good bread of Tuscany, made without salt and which does not mildew. The poem becomes our mirror, reflecting also this city. Dante writes a Comedy, not at all a Tragedy about kings and their hollow power. It is a poem of hope, a Magnificat. It is the most famous poem in the world.

Dante writes the

Commedia in exile from Florence, but with the memory of this Badia, of the little and very ancient church of St Martin beside it founded by Irish pilgrims centuries earlier, of the Bargello, of the Palazzio del Popolo (now called ‘Vecchio’, for it is seven hundred years old), of the Duomo, many of these built or planned by Arnolfo di Cambio or his father. All these fine buildings were within the walls and the gates built by Arnolfo di Cambio using the stone first built into the Ghibelline ‘towers of pride’ and within this painting. This wall for the common defense was repaired in the Renaissance, then in the Victorian period torn down to make way for boulevards for traffic. The painting below in the Cathedral, the Duomo, shows Dante outside the walls as an exile, preaching the

Commedia to his city, its gate being the same as that for Hell and for Purgatory. The three gates are Arnolfian.

Domenico da Michelino, Dante and Florence, Cathedral

On Hell Gate Dante has God write:

Per me si va nella città dolente,

Per me si va nell’etterno dolore,

Per me si va tra la perduta gente.

Giustizia mosse il mio alto Fattore:

Fecemi la Divina Potestate,

La Somma Sapienza e’l Primo Amore.

Through me you enter the city of sorrow,

Through me you go into eternal pain,

Through me you go amongst the lost people.

Justice moved my High Architect,

I was made by Divine Power,

By Highest Wisdom and by Primal Love.

But when we go the other way through the Arnolfian gate of

Purgatorio we leave behind all sorrow to enter into love – as I explained when lecturing on this poem in Attica State Prison.

The

Commedia tells us of Dante’s exile become pilgrimage, first through Hell where Dante as sinner meets many mirroring sinners, then Purgatorio where Dante shares in purgation from them with others, finally, in Paradise, where he soars into the hevens with Beatrice Portinari, daughter of Folco Portinari the founder of Santa Maria Nuova Hospital. The

Commedia as poem heals the city of Florence and ourselves. In the last canto of the

Paradiso, its Canticle of Canticles, we meet Bernard singing his hymn to the Madonna, which Filippino will show in a painting brought to the Badia in 1530, and which Professor Giorgio La Pira, Mayor of Florence, Founder of the Mass for the Poor, so much loved

Alinari

Filippino, Vision of Saint Bernard, Badia

The words of Bernard’s hymn in Dante’s

Paradiso are placed on the facade of the Misericordia, words which I read to my visitors. Then we turn to gaze upon the great Cathedral of Florence, its Duomo, Santa Maria del Fiore:

Vergine Madre, figlia del tuo figlio,

umile e alta più che creatura,

termine fisso d’etterno consiglio,

tu se’ colei che l’umana natura

nobilitasti sì, che ’l suo fattore

non disdegnò di farsi sua fattura.

Nel ventre tuo si raccese l’amore,

per lo cui caldo ne l’etterna pace

così è germinato questo fiore.

Virgin Mother, daughter of your son,

humble and higher than any creature,

fixed goal of eternal counsel,

You are she who ennobled human nature

so that the Creator

did not disdain to become your Creation.

In your womb is bound up the love

through whose warmth in eternal peace

is thus germinated this flower.

I left out of my talk in the Badia that often when I shared with gypsy mothers in the street blessed bread and postcards of Dante, like the one above, they would ask ‘Was he a saint?’ and when I said ‘No’, explaining however that he had preached to his city about mercy, they would kiss the postcard as if it were an icon and share it with their children.

All is well here. We have saved the English Cemetery. Now we must restore it. Gypsy Maria and Daniel, from Romania and who come to the Mass for the Poor, today have weeded out all the stinging nettles (I supplied them with gloves and trowels). A month ago they, with their other brother Benoni, planted two enormous boxes filled with daffodil bulbs, which will come up in the Spring. Next, I hope to teach them tomb cleaning and restoration. Unlike Hedera or Luca, they are already literate, in both Roman and Cyrillic alphabets and love reading our polyglot tombstones of English, American, Russian and Swiss burials.

A thousand blessing for Christmas, Epiphany, and 2007.